Swanage (or Swanwich, as it was once known) has probably existed since well before Roman times. The quarrying of stone has always been important, reaching its peak in Victorian Britain. Since then the town has developed into the beautiful and popular resort you see today.

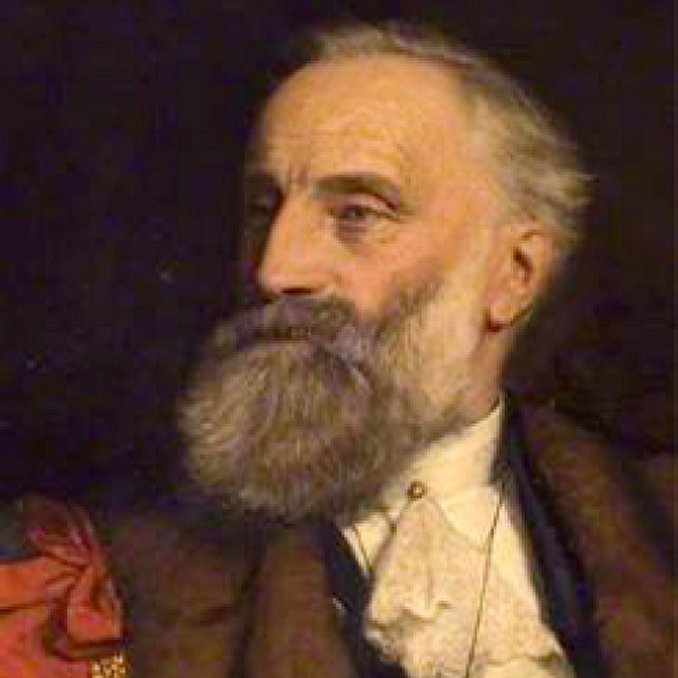

John Mowlem (1788 – 1868)

John Mowlem, founder of the international construction firm, was born at Swanage in 1788.

He was a quarryman’s son, who at the age of 17 left “with his tools on his back, to seek his way in the world”. He soon went to London and worked for prominent stonemason Henry Westmacott.

From 1816 Mowlem was foreman of all Westmacott’s London works. He later noted that “I was put over men old enough to be my father. I knew little, but I moved upwards”. In 1822 he started his own business and secured contracts for paving London’s streets.

Mowlem’s company prospered and paved many famous streets, including Fleet Street and The Strand. He also bought granite quarries in Guernsey and Aberdeen, and sailing vessels to transport the stone.

In 1845 John Mowlem retired to Swanage and left his firm in the safe hands of “my two young men”, George Burt, his nephew, and Joseph Freeman.

Mowlem devoted the rest of his life to Swanage. He gave money to charities, churches and the poor. He also invested in road improvements, a pier and in attempts to bring a railway to the town. In 1868 he died at Old Purbeck House in his 80th year.

George Burt (1816 – 1894)

George Burt was the most important figure in the history of Swanage and the town’s greatest benefactor. Through his influence Swanage changed from a coastal town dominated by stone yards to the seaside resort we see today.

He “inherited” John Mowlem’s firm and went on to rebuild many famous London landmarks before retiring to his newly built mansion in Swanage, called “Purbeck House”. George Burt was a generous man who, like his uncle John Mowlem, was determined to improve his birthplace using his own wealth.

Burt built the Town Hall, Durlston Castle and the “Great Globe”. He improved the town with new roads and shops, gas lighting, a pure water supply, and drainage. In 1885 he finally brought the railway to Swanage, a vital link before the days of the motor car.

Thomas Hardy described Burt as the “King of Swanage”, observing that he “was rougher in speech than I should have expected after his years in London”.

In 1894 George Burt died in Swanage at the age of 77 but was buried at Kensal Green Cemetery in London.

It was rightly said, “we have lost one whom it will not be merely hard, but impossible to replace”

During the 19th Century John Mowlem and George Burt rescued many architectural relics from London. These were re-erected in Swanage, soon giving the town the nickname “Old London by the Sea”.

Old London By The Sea

Town Hall

Swanage Town Hall was built by George Burt in 1882.

To adorn it he acquired the entire 17th Century stone facade from the Mercers’ Hall at Cheapside in London.

Billingsgate Fish Market

When the world famous fish market was demolished and rebuilt in 1875, George Burt rescued parts of the old building and built them into his new home, “Purbeck House” and its garden.

Cast iron balustrading can be seen on the stable yard wall, near the High Street entrance. The cast iron columns, which formerly faced the Thames, are now incorporated into Purbeck House and the Town Hall.

The tower of Purbeck House was originally topped by a flying-fish weathervane from Billingsgate. It became unsafe and can be seen today at Newton Manor on the High Street.

Most of the relics that John Mowlem and George Burt rescued from Victorian London were transported to Swanage as ballast in their firm’s stone boats.

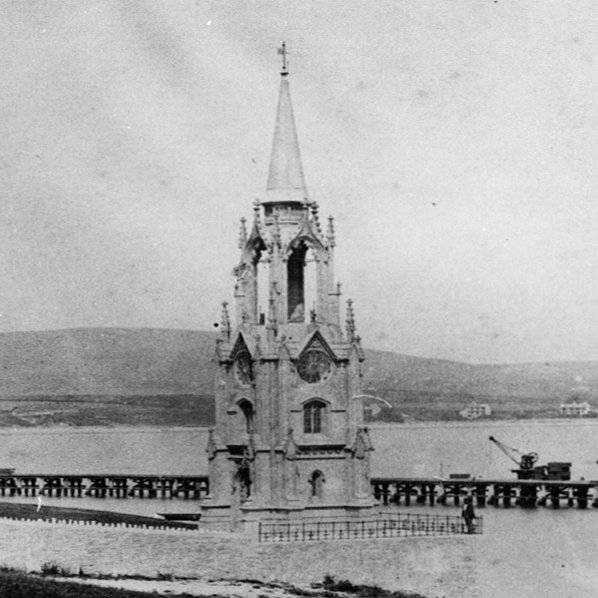

Wellington Clock Tower

Originally the Wellington Clock Tower stood on the Southwark side of London Bridge. It was built as a memorial to the Duke of Wellington in 1854.

By the 1860’s the clock tower had become “an unwarrantable obstruction” to London’s increasing traffic. Due to the traffic the clock was a bad timekeeper, and a poor tribute to the Duke, who had been a stickler for punctuality.

George Burt removed the clock tower to Swanage at no charge. It was re-erected without its clock in 1868 at The Grove, a house owned by retired London contractor, Thomas Docwra. The spire, said to be unsafe, was replaced around 1904 by the present cupola.

Bollards

The most common relics of “Old London” in Swanage are the cast iron bollards. More than one hundred bollards can be seen around the town. Some were removed for scrap metal during the Second World War, including one incorrectly marked “City of London”.

Many of those that remain have the names of individual London parishes, such as “St. James, Clerkenwell” and “St. Giles and Bloomsbury”.

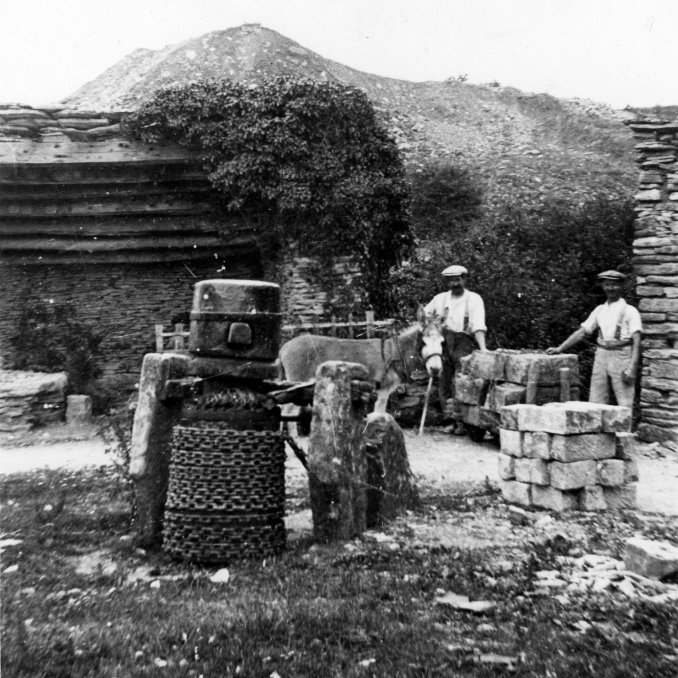

The Stone Trade

There are over seventy different beds of stone in Purbeck. The best beds have been quarried since Roman times.

After the Great Fire of London in 1666 there was great demand for Purbeck stone. As Daniel Defoe observed, “this part of the country is eminent for vast quantities of stone which is used for paving”.

The stone was extracted from cliff and inland quarries. Wooden cranes lowered stone from the cliff quarries into waiting vessels for shipment either to the stone yards at Swanage, or further afield.

Inland quarrying involved sinking an inclined shaft with tunnels or “lanes” to extract the bed of stone required. Above ground a horse or donkey turned a capstan and drew the blocks of stone up the shaft on a small cart.

Worked stone was bought by merchants and stored in yards on the seashore known as “bankers”. When sold, the stone was loaded into high-wheeled carts, taken into the sea, and transferred to small boats that were rowed out to sea-going ketches. This practice ceased after the coming of the railway in 1885.

Small, family-worked underground quarries were eventually superseded by large open-cast quarries in the 20th Century, which today provide everything from local building stone to fine restoration work in cathedrals.

Health Resort

By the early 19th Century Swanage, or “Swanwich”, was on the brink of something completely new. King George III had made sea-bathing fashionable during his visits to nearby Weymouth. Swanage too would benefit from this new pastime.

Wealthy landowner and Mr William Morton Pitt, was the first to envisage Swanage as a “watering-place”. He wanted to visit the town with his family in the summer season and thought other people of “quality” would wish to do the same. Pitt realized that to rival Weymouth or Lyme Regis, Swanage would need proper accommodation and amenities.

His first project was to turn the old Mansion House into the Manor House Hotel. This was later re-named the Royal Victoria Hotel after Princess Victoria spent a night there.

In 1825 he built Marine Villas, providing visitors with salt-water baths, and billiard and coffee rooms. This was followed by The Rookery in Seymer Road, which acted as a Customs House, shop, and library. He also built The Watch and Preventive Station near Peveril Point, housing Customs men to combat smugglers. Despite his “time and exertions unremittingly devoted to the public good”, William Morton Pitt died bankrupt in 1836, having invested much of his family fortune in developing Swanage.

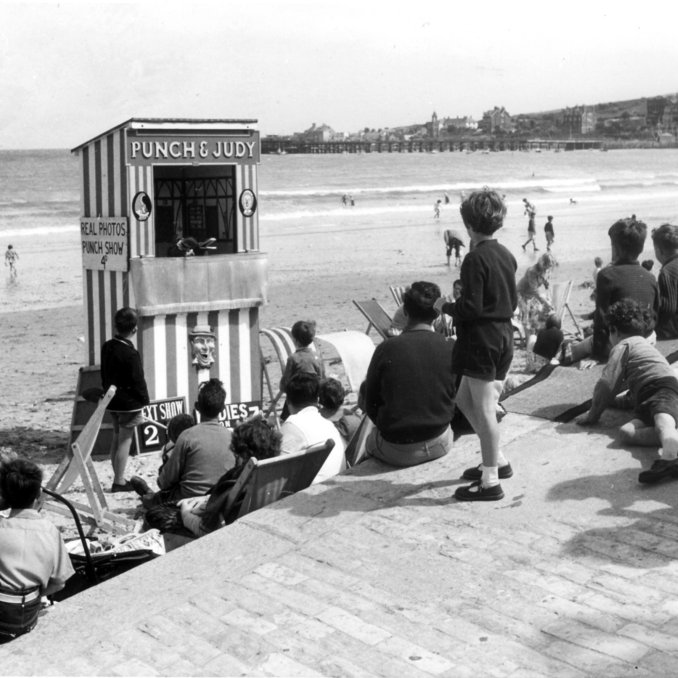

Seaside Resort

The arrival of the railway in 1885 ensured Swanage’s development as a popular tourist resort. The substantial efforts of John Mowlem and George Burt had finally been rewarded and visitors flocked into the town.

The stone yards or “bankers” on the seashore were swept away and new shops were built. The pleasure pier opened in 1896. Huge numbers of day-trippers began arriving by paddle steamer, which continued until the outbreak of the First World War in 1914.

The 1920’s and 1930’s saw Swanage recognised as “one of the leading holiday resorts on the South Coast”. This era of carefree holidays came to an abrupt end with the beginning of the Second World War in 1939.

After 1945 seaside holidays remained popular, but increasing car ownership saw the railway and paddle steamer services steadily decline. In 1966 the last paddle steamer was withdrawn and the pier fell into decay. In 1972, despite attempts to save it, the railway closed. During the 1970’s cheap overseas holidays led to the closure of many local hotels.

In recent years Swanage’s fortunes have improved. The railway has reopened, the pleasure pier restored to its former glory, and the beach is still enjoyed by people of all ages.

Shops & Traders

Until the second half of the 19th Century, Swanage was a small community which largely depended on stone quarrying and fishing for its livelihood.

The town was served by all the traditional shops and trades, from butchers and bakers to shoemakers and tailors. However, the growth of the tourist industry led to the building of new hotels and boarding houses, which in turn saw the opening of many new shops to cater for the needs of the summer visitors.

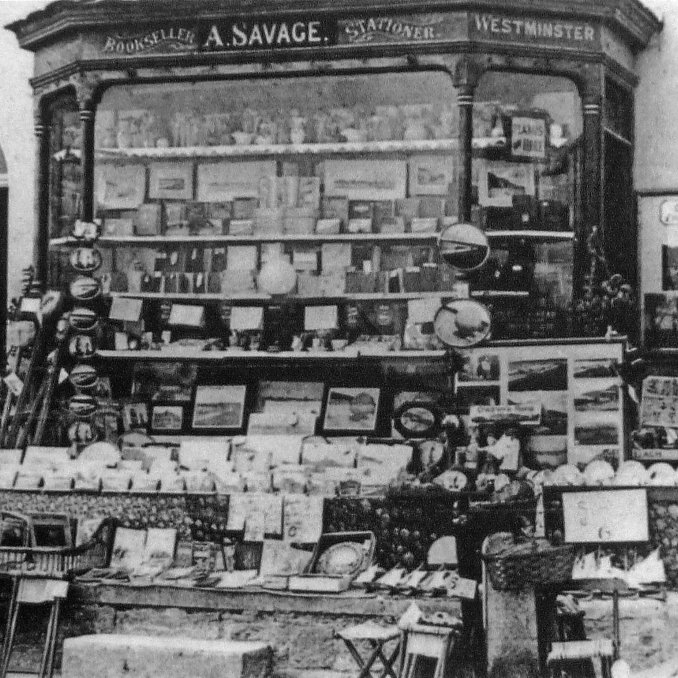

Souvenir shops offered visitors all sorts of gifts as mementoes of their trips to Swanage, including local picture postcards to send home to family and friends. The postcard boom in Britain reached its peak in the Edwardian era with an estimated 260 million postcards being sent in 1906 alone.

Until the coming of the railway in 1885 most shops were situated in the High Street. The new Station Road developed slowly, with the first shops not being built until 1893. Following the clearance of the stone yards or “bankers” from the seashore, more new shops were also built in Institute Road.

By the 1920’s the Town Centre looked much as it does today, with Station Road generally regarded as the main shopping street.

The Second World War

Swanage suffered badly during the Second World War, chiefly from “hit-and-run” lightning raids by Nazi planes swooping in from the sea. Swanage suffered six major air raids in which twenty people were killed.

Beach defences consisted of barbed wire, scaffolding and concrete anti-tank blocks known as “dragons’ teeth”. Sections of the two piers were also removed to hamper a possible invasion.

The Tourist Information Centre on Shore Road became the Air Raid Precautions (ARP) headquarters during 1939-40, and was later used by the members of the local Home Guard.

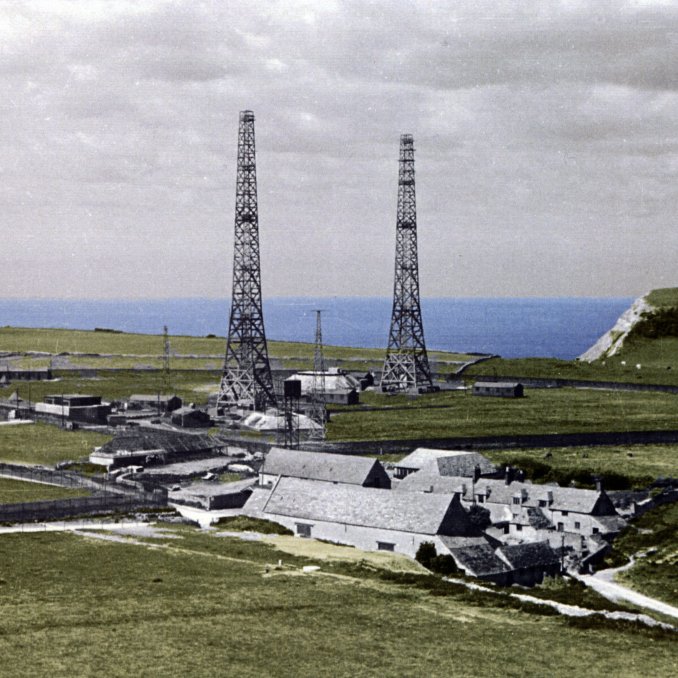

From 1940-42 Purbeck was the nerve centre of Britain’s radar research, when the Telecommunications Research Establishment (TRE) was based at Worth Matravers near Swanage.

During 1944 Swanage and Studland became a vast training area for British and American troops preparing for D-Day and the invasion of Europe. These preparations were personally inspected by King George VI, the Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, and the Allied Commanders, General Montgomery and General Eisenhower.

RADAR Development In Purbeck

The development of radar was key to the success of the UK in the Battle of Britain and continued to swing the balance in World War II until the allies were ultimately successful. From May 1940 to May 1942, pioneering research into radar was undertaken at Worth Matravers in the Isle of Purbeck. Talented scientists were recruited from top universities, and many ideas were developed which went on to form the basis of the electronics industry we take for granted today.

Radar defended Britain by giving early warning of approaching hostile aircraft. Fighter aircraft could then be scrambled and guided to intercept them.

Radars were installed in aircraft. These helped to intercept hostile aircraft at night, and to detect ships and partially exposed submarines. This proved a trump card in the Battle of the Atlantic, combatting the treat from German U-boats to convoys from the United States.

Later in the war, airborne radar and radio navigation aids helped bombers locate their targets more accurately. Developments in jamming and fooling German radars played an important role in D-Day. Linked to a supply of false intelligence, this helped mislead the Germans about our invasion strategy and saved many British and US lives.

In the early 1930s it was widely known that radio waves were reflected by aircraft and ships could be detected. However, it was in the UK that concerns about air defence were acted on by making a major investment to develop a radar warning system. This, together with breaking the code of the German Enigma machine at Bletchley Park, undoubtedly tipped the balance of World War II in favour of the UK and its allies.

For more information go to the Purbeck Radar Museum Trust website www.purbeckradar.org.uk